A version of this essay appeared in Book review by The New York Times..

The cloud is a spell against indifference, a symbol water circulation what makes this planet a living world, capable of trees and tenderness, a great cosmic sigh at the improbability of such a world existing, that in the cold expanse of space-time dotted with billions of billions of other star systems there is nothing like it as yet as we know it.

The clouds are almost as old as this world, having formed when primordial volcanoes first released the chemicals of a molten planet into the sky, but their science is younger than the steam engine. In the early 19th century, chemist and amateur meteorologist Luke Howard, still in his early twenties, noticed that clouds took on certain shapes under certain conditions. He decided to develop a classification system modeled on Linnaeus’ newly popular taxonomy of the living world, listing three main classes cumulus, stratusAND cirrusand then weaving them into different subtaxonomies.

When the German translation reached Goethe, the polymathic poet with a passion for morphology was so inspired that he sent fan letters to the young man who “distinguished cloud from cloud” and then composed a set of verses for each of the major classes. It was Goethe’s poetry, translating the lexicon of a little-known science into the language of miracles, that popularized the names of clouds used today.

A century and a half later, six years earlier Rachel Carson With her book, she awakened contemporary ecological awareness Silent spring and four years later The sea around us won her a National Book Award for “a work of scientific accuracy, presented with poetic imagination” – a television program Omnibus he approached her with a proposal to write “something about heaven” in response to a request from a young viewer.

This became the title of an episode broadcast on March 11, 1956, a soulful serenade to cloud science that exuded Carson’s ethos of “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe around us, the less we will be tempted to destroy our race.”

Although known for her books about the sea, Carson’s literary career began in the air. She was only eleven years old when her short story “Battle in the Clouds” – a tale inspired by her brother’s time in the Army Air Corps during World War I – was published in a popular young people’s magazine Saint Santa Claus, where Edna St.’s early writings were also published. Vincent Millay, F. Scott Fitzgerald and E.E. Cummings. Despite the family’s modest means – a neighbor remembers dropping by at dinner time to find the Carsons gathered around a bowl of apples – she enrolled at an all-women’s college on a $100 scholarship from a state competition, intending to study literature at a time when fewer than four percent of women have completed a four-year university degree.

And then, just as all the great changes were slipping through the back door of the mansion of our plans, her life took a turn that shaped her future and literary history.

To meet college requirements that she had been deferring for a year, Carson took an introductory biology course. She found herself enchanted by both the subject and its teacher: Miss Mary Scott Skinker, who wore miniskirts, taught cutting-edge disciplines such as genetics and microbiology, and gave fascinating lectures on evolution and natural history that awakened in her students an awareness of the interdependence of life, who would never leave Carson. At the age of nineteen she changed her major to biology. However, she never lost her love for literature. “I always wanted to write,” Carson told her lab partner late one night. “Biology gave me a reason to write.” She also wrote poems, submitting them to various magazines, receiving rejection after rejection.

Somewhere along the way, she followed Skinker to the Woods Hole Marine Biological Observatory and then worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, writing reports that her boss found it too lyrical to a government publication and encouraged her to come forward Atlantic MonthlyCarson realized that poetry existed beyond verse in countless forms, that the task of science was to discover the “wonder, beauty, and majesty” inherent in nature. A lifetime later, she rose from the table she shared with poet Marianne Moore to accept the National Book Award those words: :

The aim of science is to discover and illuminate the truth. And that, I think, is the purpose of literature, whether biography or history or fiction; Therefore, it seems to me that there cannot be separate scientific literature.

Carson believed that if there was poetry in her writing, it was not because she “intentionally put it there,” but because no one could write about nature truthfully “without poetry.”

It was a radical idea – that truth and beauty do not compete with each other, but are mutual, and that writing about science sensitively does not mean diminishing its authority, but deepening it. Rachel Carson modeled new possibilities for future generations of writers, blurring the line between where science ends and poetry begins in the work of wonder.

This was the ethos she espoused as she “wrote the wind in the sky,” detailing the science of each of the major classes of clouds and celebrating them as “cosmic symbols of a process without which life itself could not exist on earth.”

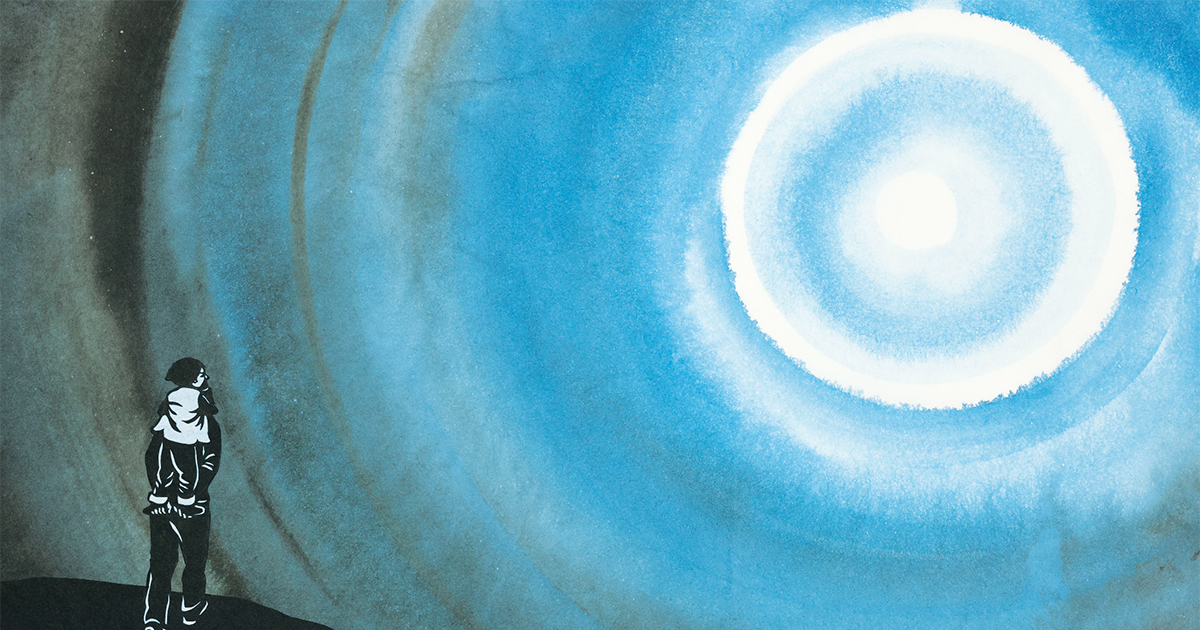

After stumbling across excerpts from Carson’s long-lost TV script Orion magazine, artist Nikki McClure — who, like Carson, grew up in nature, worked for a time in the Ecology Department, and enjoys watching birds every day under the cedar canopy next to her house — wanted to find the entire original and bring it to life in lyrical illustrations: Something about heaven (public Library) born.

Known for her unique paper cut art, with its stark contrasts and sharp contours, took on the creative challenge of finding a completely new technique for channeling the softness of the sky. Using paper from an old trip to Japan and sumi ink that she liberally applied with brushes, she allowed the gentle effects of gravity and fluid dynamics to merge and blur the mostly blue and black tones into textured layers – a process of “possibility and chance.” ” Then, as he recalls in the illustrator’s note at the end of the book, she “cut out the images with paper, not just from it”: “We talked to the newspaper about what might happen.”

What emerges is a delicate visual poem as boldly defying categories as Carson’s writing.

Although Carson never wrote directly for children, she wrote in the language of children: a miracle. Among the boxes of mail from Beinecke’s fans is a letter from a geology professor who, after comparing her with Goethe, told her how delighted his eight-year-old son was with her words.

Less than a year later Something about Heaven aired, Carson adopted her twice-orphaned grandson Roger, a little boy who played with McClure’s illustrations. It began as an article for Woman’s Home Companion and was later expanded into a posthumously published book A sense of wonderShe wrote:

A child’s world is fresh, new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. Our misfortune is that in most of us this keen vision, this true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had the influence of a good fairy who was to preside over the baptisms of all children, I would ask that her gift to every child in the world be such indestructible delight that it would last throughout life, as a sure antidote to the boredom and disappointment of later years, the sterile preoccupation with artificial things, alienation from the sources of our strength.

Couple Something about heaven with an animated story where the clouds get their names fromand then visit Carson again writing and the loneliness of creative work AND 문화상품권 현금교환.